Textile Cost Impact Calculator

Calculate Your Competitiveness

Compare your current production costs against 1990 benchmarks to identify competitiveness gaps. All metrics reflect industry averages.

Competitiveness Assessment

Key Insights

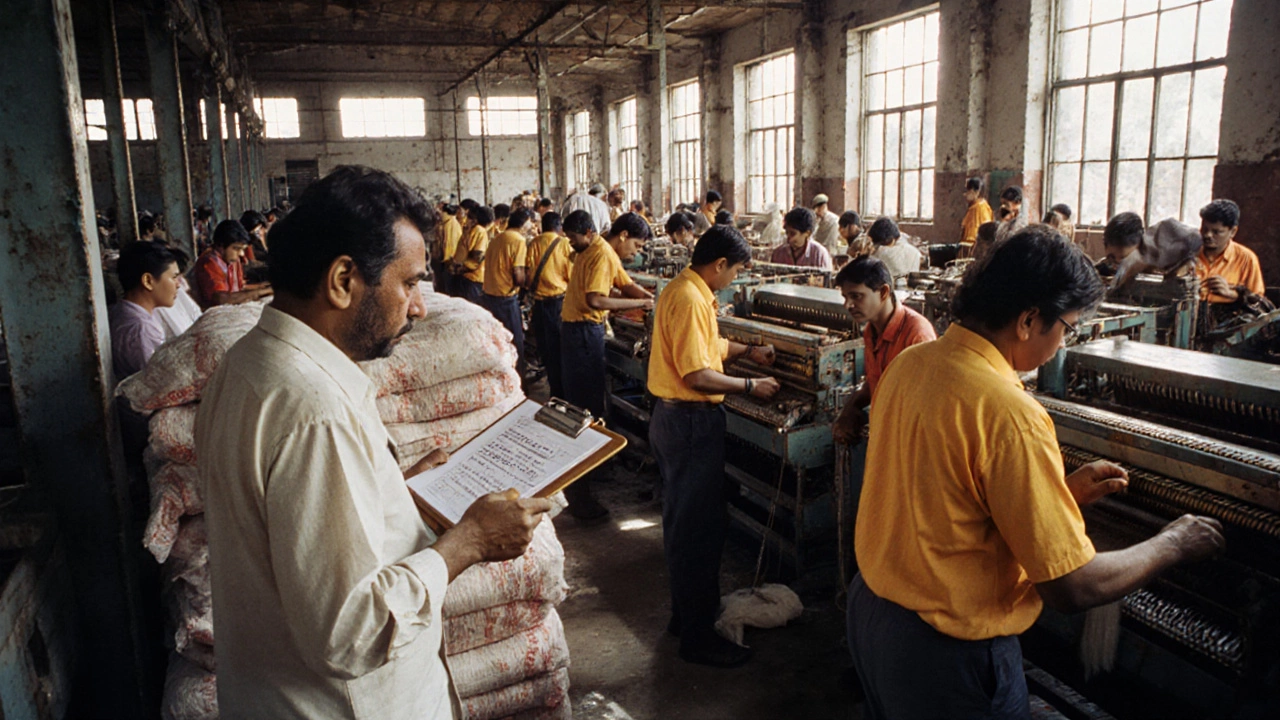

When analysts look at the downfall of a once‑thriving sector, the Indian textile industry refers to the network of cotton, wool, silk and synthetic fabric producers that employed millions across the subcontinent offers a vivid picture of how policy, cost pressure and global forces can combine to topple an economic heavyweight.

Historical backdrop: From colonial roots to global contender

During the British Raj, India supplied raw cotton to mills in Manchester, while local handloom weavers struggled to compete. After independence, the government launched the Integrated Textile Parks scheme (1975) and set up the Textile Ministry to nurture domestic capacity. By the early 1990s, India ranked among the top five textile exporters, thanks to abundant cotton, low‑cost labor and a massive internal market.

Policy shifts and trade liberalisation

In 1991, India embraced economic liberalisation under the New Economic Policy. Tariffs on raw yarn and finished fabrics fell from 30% to under 10% within five years. While the move opened doors to cheaper inputs, it also exposed domestic mills to a flood of Chinese and Pakistani products that were cheaper and technically superior.

Key policy changes that accelerated the decline:

- Removal of export subsidies for cotton yarn in 1994.

- Reduction of import duties on synthetic fibres, allowing bulk imports from South Korea and Taiwan.

- Relaxation of the "Make in India" incentives for textiles, shifting focus to high‑tech sectors.

Rising labor and raw‑material costs

For decades, low wages kept unit economics attractive. By the late 2000s, minimum wages in major textile hubs (e.g., Tirupur, Surat) rose by 60% due to inflation and political pressure. Simultaneously, cotton yields fell after the 2009 monsoon deficit, pushing farm‑gate prices from INR 40/kg to over INR 80/kg by 2012.

These cost spikes hit small‑scale units hardest because they lacked the bargaining power of large conglomerates. Many turned to informal labour, which sparked disputes and further reduced productivity.

Global competition and trade dynamics

China’s rise as the world’s factory dwarfing India’s export share from 12% in 1995 to under 6% by 2020. The World Trade Organization’s 2005 agreement on textiles and apparel eliminated the quota system, flooding markets with ultra‑low‑price garments.

Three competitive disadvantages stood out:

- Scale: Chinese mills operated at capacities exceeding 30,000 spindles per plant, versus an Indian average of 5,000.

- Technology: Automation levels in China reached 45% by 2018, while Indian factories lagged at 12%.

- Supply chain speed: Chinese logistics networks delivered raw material to finished goods within 48 hours, whereas Indian lead times often exceeded a week.

Technological lag and automation deficit

Investments in modern looms, computer‑aided design (CAD) and ERP systems were sporadic. The 2008 "Technology Up‑gradation Fund Scheme" allocated INR 1,500 crore, but only 15% of eligible units accessed the funds due to bureaucratic delays.

Consequences of low automation:

- Higher defect rates (average 3.8% versus 1.2% in leading Asian peers).

- Inability to switch quickly to high‑mix, low‑volume orders demanded by fast‑fashion brands.

- Energy inefficiency: older machines consumed 30% more electricity, raising operating costs.

Structural issues in small‑scale units

More than 70% of Indian textile output came from units employing fewer than 50 workers. These producers faced three chronic problems:

- Inadequate power supply-average downtime of 12 hours per month.

- Lack of access to credit; the average loan size was INR 3 lakh, insufficient for capital upgrades.

- Fragmented supply chains; many relied on middlemen for yarn procurement, eroding margins.

When larger firms consolidated or moved offshore, these micro‑enterprises had no runway to survive.

Market demand changes and fashion cycles

Fast‑fashion giants such as Zara and H&M accelerated style turnover to 4‑6 weeks. Indian manufacturers, still geared toward 3‑6 month production cycles, missed the window to supply timely collections. Additionally, a shift toward synthetic blends reduced demand for traditional cotton fabrics, a segment where India once held a monopoly.

Key takeaways and forward‑looking lessons

Understanding why the sector fell apart helps today’s manufacturers avoid similar pitfalls. Below is a quick checklist for anyone involved in textile production, whether in India or elsewhere:

- Align technology roadmaps with global automation benchmarks (target >30% automation within five years).

- Secure diversified financing to fund capital upgrades without over‑reliance on government schemes.

- Develop flexible production lines that can switch between fabric types and order sizes within weeks.

- Invest in reliable power and logistics partnerships to cut downtime.

- Monitor global trade policies; maintain a balanced mix of domestic and export markets.

By treating these factors as a cohesive ecosystem rather than isolated challenges, firms can build resilience against future shocks.

Comparison of pre‑1990 and post‑1990 industry metrics

| Indicator | Pre‑1990 | Post‑1990 |

|---|---|---|

| Export Share (global textile market) | 12% | 6% |

| Average Labor Cost (INR/day) | 150 | 240 |

| Cotton Yield (kg/ha) | 500 | 420 |

| Automation Level (%) | 8 | 12 |

| Average Plant Size (spindles) | 5,800 | 4,900 |

Frequently Asked Questions

What were the main policy changes that hurt the industry?

The 1991 liberalisation lowered import duties, removed export subsidies, and opened the market to cheap Chinese fabrics, all of which squeezed profit margins for Indian producers.

Did labor costs rise dramatically?

Yes. Minimum wages in key textile hubs jumped about 60% between 2005 and 2015, outpacing productivity gains and eroding competitiveness.

How did technology gaps affect quality?

Outdated looms produced higher defect rates-around 3.8% versus 1.2% in more automated Asian facilities-making Indian fabrics less attractive to premium buyers.

Are small‑scale units still viable?

Survival is possible only with niche specialization, reliable power, and access to affordable credit for modernization.

What can current manufacturers learn from this collapse?

Diversify markets, invest in automation, keep a close eye on global trade policies, and build flexible supply chains to adapt to fast‑changing fashion demands.

In short, the fall of the Indian textile industry was not a single event but a chain reaction of policy shifts, cost pressures, technology lag, and market mis‑alignment. By addressing each link proactively, today’s manufacturers can turn a cautionary tale into a roadmap for sustainable growth.