Chemical Production Cost Calculator

Dr. A.V. Rama Rao revolutionized chemical manufacturing in India by developing cost-effective processes using locally available materials and simplified equipment. This calculator estimates the potential savings you could achieve by implementing his approach versus traditional methods.

Input Your Production Data

Enter your production data to see potential savings from Rama Rao's methods.

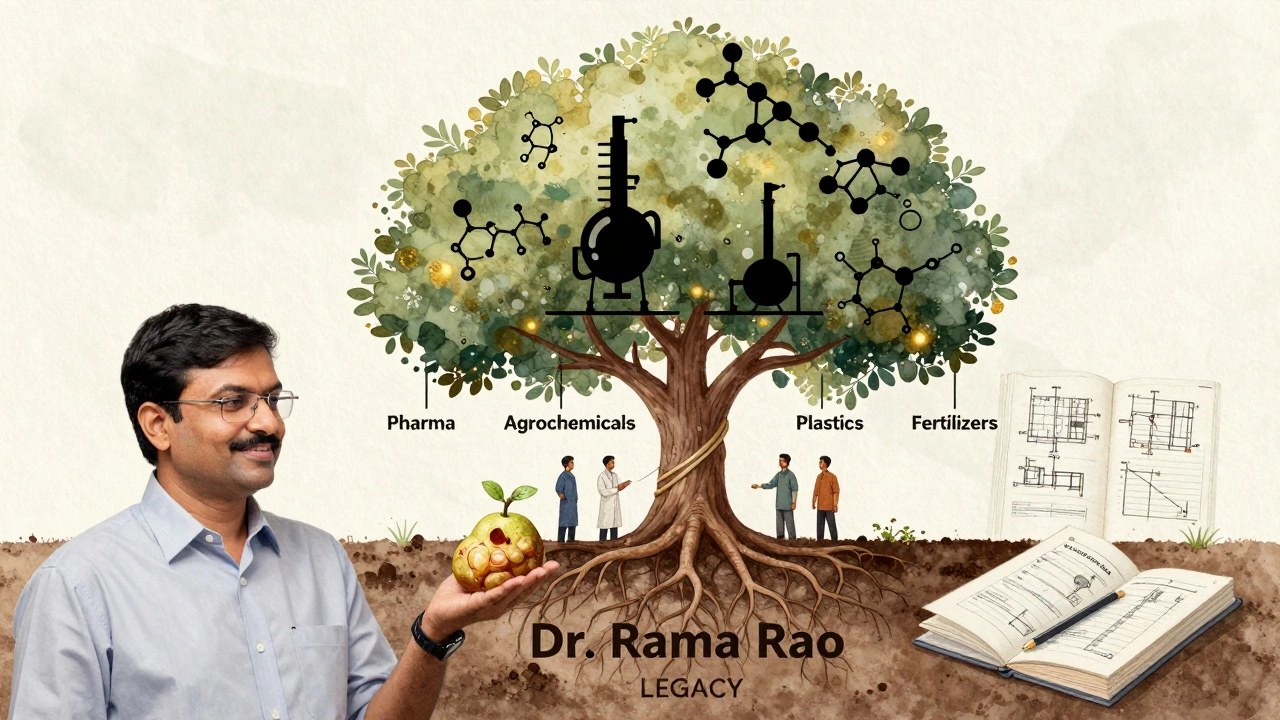

When people ask who the God of Chemistry in India is, they’re not looking for a mythological figure. They’re asking about the person who shaped modern chemical manufacturing in India - the quiet force behind the country’s rise from importing basic chemicals to becoming a global exporter of pharma intermediates, agrochemicals, and specialty chemicals. That person is Dr. A.V. Rama Rao.

Who Was Dr. A.V. Rama Rao?

Dr. A.V. Rama Rao wasn’t a flamboyant entrepreneur or a media darling. He was a professor at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bangalore, a researcher with a stubborn focus on practical chemistry, and a mentor to hundreds of engineers who went on to run India’s biggest chemical plants. Born in 1938 in Andhra Pradesh, he studied chemistry at Osmania University and later earned his Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota in the early 1960s. He returned to India not to stay in academia, but to fix what was broken: India’s reliance on foreign chemical suppliers.

At the time, India imported 80% of its basic industrial chemicals - from solvents to catalysts - even though it had the raw materials and the engineers. Rama Rao saw this as a national vulnerability. He didn’t just teach organic synthesis; he built systems. His lab at IISc became a factory for ideas that could be scaled. He worked with small chemical units in Hyderabad and Chennai to design low-cost, high-yield processes for making compounds like phenol, formaldehyde, and aniline - the building blocks of plastics, dyes, and medicines.

Why He’s Called the God of Chemistry

The title isn’t about worship. It’s about impact. By the 1980s, over 60% of India’s chemical production used processes developed or refined under Rama Rao’s guidance. His team cracked the code on making high-purity ethanol from molasses - a breakthrough that saved India millions in foreign exchange. He didn’t patent most of his work. He published papers, trained students, and handed over blueprints to public sector units like Hindustan Inorganic Chemicals and Indian Petrochemicals Corporation Limited (IPCL).

His real genius was in simplification. While Western chemists used expensive catalysts and high-pressure reactors, Rama Rao’s teams built reactors from mild steel, used locally available catalysts like lime and clay, and ran processes at lower temperatures. One of his most famous designs - a continuous flow reactor for making ethylene dichloride - cut production costs by 40% and became the standard in Indian chlor-alkali plants. By the 1990s, India went from importing $2 billion in chemicals annually to exporting $1.8 billion.

His Legacy in Today’s Chemical Industry

Today, India is the third-largest producer of pharmaceutical ingredients in the world and the fourth-largest exporter of agrochemicals. Companies like Dr. Reddy’s, Sun Pharma, and Jubilant Life Sciences all trace their early R&D roots to engineers who studied under Rama Rao or used his published methods. His influence is in the DNA of India’s chemical supply chain.

Take the case of chlor-alkali plants. Before Rama Rao, Indian plants used mercury cell technology - expensive, toxic, and inefficient. He pushed for membrane cell technology using locally made ion-exchange membranes. Today, over 90% of India’s chlorine production uses membrane cells - a direct result of his advocacy and pilot projects in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu.

Even in niche areas like specialty esters for perfumes and plasticizers, Indian manufacturers use formulations based on his 1978 paper on esterification kinetics. His work on catalyst deactivation helped small units in Bhopal and Ankleshwar extend the life of their reactors by 300% - a game-changer for businesses operating on tight margins.

What Made Him Different?

Most scientists chase publications. Rama Rao chased outcomes. He didn’t care about citations; he cared about whether a chemical plant in Madurai could run profitably. He spent months living in small factories, watching operators, fixing leaks, and redesigning distillation columns by hand. He once told a student: “If your reaction doesn’t work in a 50-liter batch with a rusty stirrer, it’s not ready for the world.”

He also refused to work with companies that didn’t train their workers. He believed chemistry wasn’t just about molecules - it was about people. He insisted that every plant he advised had a basic chemistry training program for shift supervisors. That’s why, even today, many small chemical units in India have a “Rama Rao Rule” posted on their walls: “Safety first. Cleanliness second. Efficiency third. Profit fourth.”

Who Else Matters in India’s Chemical Story?

While Rama Rao is the most widely recognized figure, he didn’t work alone. Other key names shaped the industry:

- Dr. K. R. Sridhar - Developed India’s first indigenous pesticide synthesis route for endosulfan in the 1970s, which became the backbone of domestic agrochemical production.

- Dr. P. S. Raman - Led the team that scaled up the production of polyethylene glycol (PEG) from petroleum feedstocks, enabling the growth of pharma and cosmetics industries.

- Dr. S. K. Gupta - Pioneered low-cost water treatment chemicals using natural coagulants like Moringa seed extract, adopted by municipal plants across rural India.

But none of them had the same breadth of influence across sectors - from pharma to plastics to fertilizers - as Rama Rao. His work touched every major branch of chemical manufacturing.

Why This Matters Today

India’s chemical industry is now worth over $200 billion and growing at 8% annually. But it’s not just about size. It’s about resilience. During the pandemic, when global supply chains broke, India became the go-to source for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). That wasn’t luck. It was the result of decades of building local expertise - much of it rooted in Rama Rao’s philosophy: make it simple, make it local, make it reliable.

Today’s startups in chemical manufacturing - like those making biodegradable polymers or green solvents - still follow his approach. They avoid over-engineering. They test in small batches. They source raw materials within 500 km. They train their operators before they touch a reactor. That’s the Rama Rao way.

His Unfinished Work

Rama Rao passed away in 2015, but his biggest challenge remains unaddressed: the gap between lab-scale innovation and industrial adoption. Many Indian startups still struggle to scale chemical processes because they focus too much on novelty and too little on robustness. Rama Rao would have told them: “Don’t invent a new reaction. Make the old one cheaper, safer, and easier to run.”

There’s also the issue of environmental compliance. His early work ignored pollution control because it wasn’t a priority then. Today, chemical plants face strict norms on waste discharge and emissions. The next generation of chemical leaders must build on his foundation - but with sustainability baked in from day one.

Final Thought

There’s no statue of Dr. A.V. Rama Rao in Delhi. No government award named after him. But if you walk into any chemical plant in Gujarat, Maharashtra, or Tamil Nadu, you’ll see his fingerprints - in the way the reactors are arranged, in the training manuals, in the quiet confidence of the plant supervisor who knows exactly how to adjust the reflux ratio without a manual.

He wasn’t a god. He was a teacher. And that’s why his legacy endures.

Who is considered the God of Chemistry in India?

Dr. A.V. Rama Rao is widely regarded as the God of Chemistry in India. He was a professor at IISc Bangalore who revolutionized chemical manufacturing by developing low-cost, scalable processes for essential chemicals like phenol, aniline, and ethanol. His work enabled India to move from importing chemicals to exporting them, and his methods are still used in thousands of plants across the country.

Did Dr. Rama Rao invent new chemicals?

He didn’t invent new molecules. Instead, he invented better ways to make existing ones - cheaper, safer, and at scale. His breakthroughs were in process design, not molecular discovery. For example, he redesigned the production of ethylene dichloride using low-cost materials and lower pressure, making it viable for small Indian factories.

Is there a formal title or award called ‘God of Chemistry’ in India?

No, there is no official title or government award with that name. The term is used informally by engineers, plant operators, and industry veterans to honor his unmatched impact on chemical manufacturing. It’s a grassroots honor, not a bureaucratic one.

How did Dr. Rama Rao influence India’s pharmaceutical industry?

His work on synthesizing key intermediates like chlorinated compounds and aromatic amines laid the foundation for India’s API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) industry. Companies like Dr. Reddy’s and Sun Pharma started by using his published methods to produce generic drug precursors locally. Without his cost-reduction models, India wouldn’t be the world’s third-largest API producer today.

Are there any books or documentaries about Dr. Rama Rao?

There are no mainstream books or documentaries, but several IISc alumni have written memoirs referencing his work. The Indian Chemical Society published a technical tribute in 2016 titled “Process Innovations in Indian Chemical Industry,” which includes 12 of his key papers. His lecture notes from the 1980s are still used in chemical engineering courses at IITs and NITs.

What can modern chemical startups learn from Dr. Rama Rao?

Startups should focus on making proven processes better - not inventing new ones. Rama Rao’s rule was simple: if you can’t run it in a 50-liter reactor with local materials and unskilled labor, it’s not ready. Avoid over-engineering. Prioritize reliability over novelty. Train your operators. Build for the Indian context - not Silicon Valley.